Should NATO promise Putin security for peace in Ukraine?

Last month, French President Emmanuel Macron hit the headlines when he suggested that the West should provide Russia with, quote, "security guarantees" in the event of a negotiated settlement over Ukraine, which would basically involve promising Putin not to expand NATO further eastwards or deploy weapons or troops near Russia's territory. Unsurprisingly, Macron's comments provoked outrage in Ukraine. Olekiy Danilov, secretary of the Ukrainian National Security and Defense Council, described Macron's ideas as "carpet diplomacy," while Mykhailo Podolyak, one of Zelensky's main advisers, suggested that the world should instead be seeking security guarantees from Russia.

Nonetheless, this isn't an unprecedented idea. The US provided Japan with security guarantees of a sort in the aftermath of World War Two with the 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which required US forces stationed in Japan to defend Japan in the event of a foreign invasion, and more recently, German Chancellor Olaf Schulze alluded to something similar only a few days before when he suggested that Europe should return to the pre-war peace order with Russia and resolve, quote, all common security issues. So in this article, I thought I'd try and figure out, in the event of a negotiated settlement, what the pros and cons are for the West providing security guarantees to Russia.

As we see it, there were basically three arguments against providing security guarantees to Russia. The first is a kind of moral argument that Putin and the Kremlin don't deserve to incur any kind of benefit from their invasion. The second is a deterrent argument that granting concessions to Russia will only encourage Putin and other dictators to engage in further wars of aggression in the future. The third argument is that providing the Kremlin with NATO-related security guarantees would be to tacitly endorse Putin's "spheres of influence" narrative, which claims that Russia was provoked into invading Ukraine by NATO's eastward expansion into Russia's sphere of influence, which is, well, dubious at best. Let's start with the moral argument, which is the one Ukrainian officials usually appeal to when they're resisting Macron's dovish suggestions, largely because it's probably the most politically powerful argument.

This is what Dunleavy is doing when he invokes the Nuremberg trials and talks about the Ukrainian blood on Putin's hands. The idea here is that if the West provides Russia with security guarantees, say, by agreeing not to accept Ukraine into NATO or deploying certain weapon systems on NATO members bordering Russia, then Putin will have benefited in some way. The Russian president has long complained about NATO's eastward expansion, and if his invasion ends up guaranteeing against this, Putin will have gained something from his invasion. For many people, especially Ukrainians, there's something morally unpalatable about essentially rewarding Putin for causing untold amounts of suffering across the European continent.

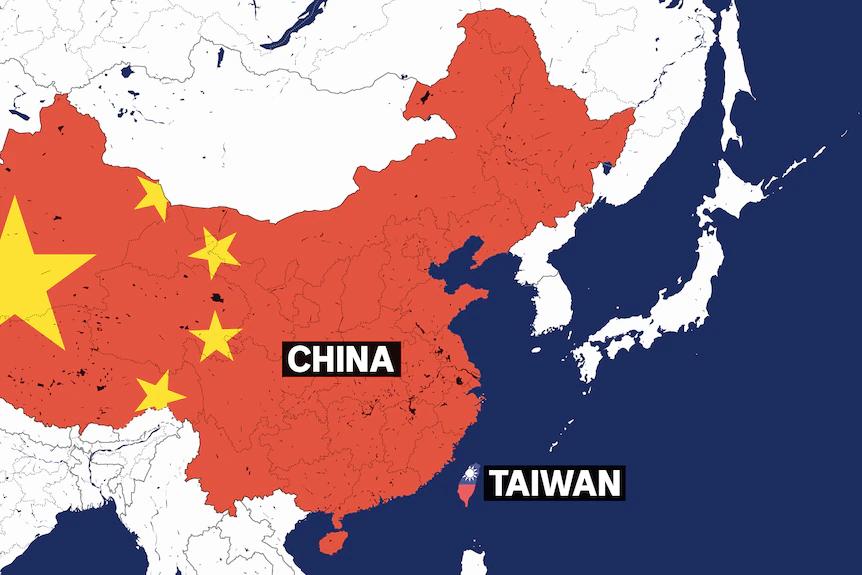

The second argument is that rewarding Putin in this way will encourage him and other ambitious neo-imperialists to stage similar wars of conquest in the future. If Putin feels he gained something from invading Ukraine this time, what's to stop him doing it again? Similarly, if someone like, say, Xi Jinping sees that invading smaller neighbors pays dividends, then they might be encouraged to take a pot at Taiwan, safe in the knowledge that even if the military massively underperforms, as the Russian military has in Ukraine, the West will eventually cave to your security demands, however unreasonable they may be. And the third argument is about exactly that Putin "spheres of influence" narrative, which motivates his concerns about NATO-related security guarantees and claims that Russia was provoked into invading Ukraine by NATO's eastward expansion. Some people argue that providing Putin with security guarantees would amount to tacitly endorsing his narrative, despite the fact that it's pretty dubious. While NATO has indeed expanded eastward since its inception in 1949, this isn't so much because the Americans wanted to encroach on Russia's spheres of influence but rather because many European countries independently expressed their intention to sign up for the alliance, largely because it's proven arguably the most successful defensive military alliance in history.

Now, whether or not you're sympathetic to Putin's narrative will depend on lots of things, including whether you're more of a realist or a liberal and whether you believe the Soviet or American accounts of NATO's early history. But lots of people argue that the West shouldn't endorse such dubious narratives. Not only would this be in some sense disingenuous, after all, but it would involve endorsing a narrative that most Western politicians take to be false for instrumental reasons. But the international community also has an interest in maintaining a high bar when it comes to justifications for war and tacitly accepting Putin's spheres of influence. Justification won't help. So those are the arguments against providing security guarantees to Putin. What about the arguments in favor of doing so?

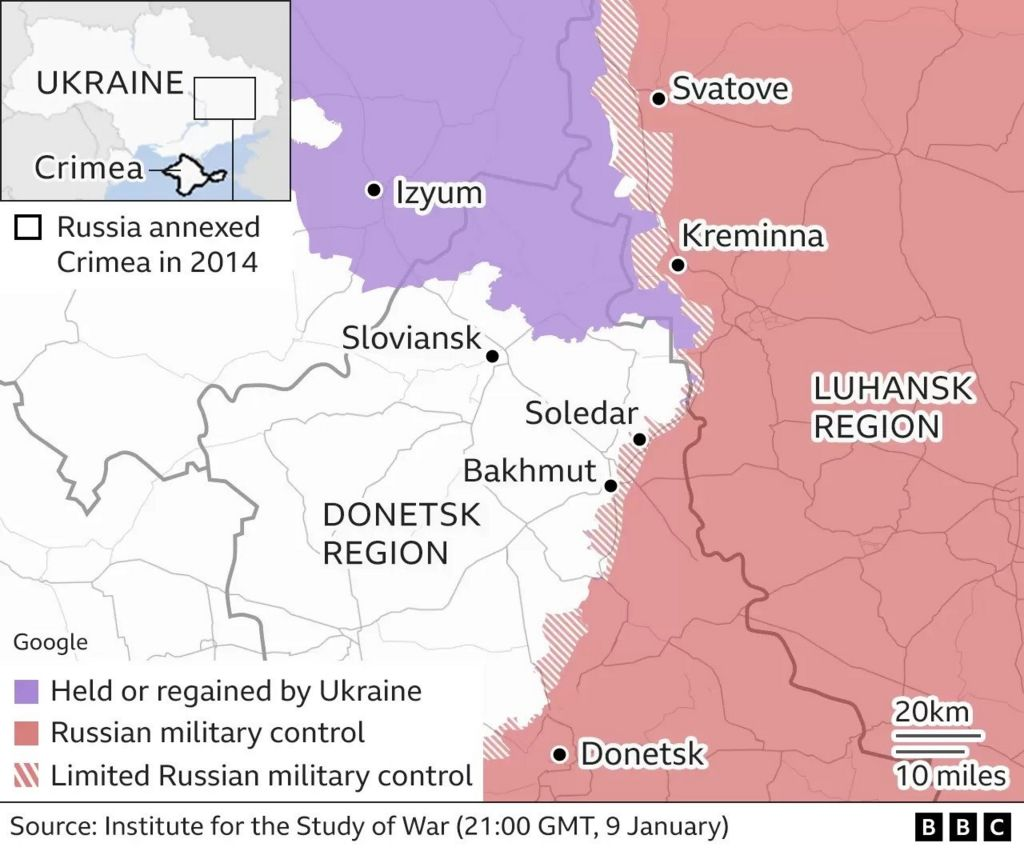

Well, as we see it, there are two main arguments in favor of providing Putin with security guarantees. First, it might make a successful peace negotiation more likely. And second, it might make any peace more likely to hold in the future. Let's start with the first one: that it'll make a peace settlement more likely. Essentially, some people, usually self-described realists, argue that any peace settlement will ultimately require concessions by both sides and that, as a form of concession, security guarantees open the door for a successful peace settlement. If you accept this line of reasoning and believe that a peace settlement is indeed a good idea, then offering security guarantees makes sense. Now, most Ukrainians don't buy this argument, both because they consider calls for peace premature given the state of affairs on the battlefield and because they consider conditions on Ukraine's relationship with NATO an unacceptably high price for peace. But this is presumably what Macron was thinking about in early December.

The second argument is that security guarantees make a peace settlement more likely to survive. Essentially, some people, including more dovish Western politicians, worry that if Putin fails to honor the security guarantees, then his continuing anxieties about NATO enlargement and the political pressure on him will make a renewal of violence more likely in the future. On the other hand, if the West agrees not to expand NATO further or maybe restrict deployments on NATO's eastern flank, Putin might feel less threatened and so be less likely to restart the conflict. Again, we should say that Kiev doesn't accept this line of reasoning, and both Danilov and Podolyak have argued that, in reality, security guarantees for Ukraine and perhaps Russia's demilitarization would be a better way to stabilize the conflict. But Macron presumably thinks that as long as Russia's total demilitarization looks unlikely, a stable peace will instead require a settlement acceptable to Moscow.

Comments