Putin could go to jail for what he did in invasion of Ukraine

According to well-evidenced reports, Vladimir Putin has presided over some pretty horrendous stuff: the bombing of maternity hospitals and kindergartens; the indiscriminate shelling of civilian areas; and attacks on fleeing refugees. In response, a whole host of big-name politicians, including the Ukrainian foreign minister and former UK prime ministers John Major and Gordon Brown, have insisted that he should be tried for war crimes, with even Biden weighing in on the issue. There are broadly four ways that Putin could be tried for his crimes: the international criminal court, the UN tribunal, a military tribunal, and domestic legislation. Let's take a look at these by one, starting with the international criminal court, ICC.

This route does make the most sense. It is mainly because it was set up with the express purpose of prosecuting individuals who commit atrocities but who are not tried by their home nation. As such, this is effectively a court of last resort. And, given that Putin is the law in Russia, it's almost unthinkable that he'll face any sort of domestic punishment, so the ICC could be a good option. It is other international courts, like, say, the International Court of Justice, but the key difference between the ICC and other courts is that the ICC can try individuals. For example, the International Court of Justice is more there to be an arbiter between states. So to try Putin and not Russia generally, we'd need something like the ICC.

But there is a slight problem. The ICC only has jurisdiction over countries that have ratified its treaty, and Russia, unfortunately, is not one of those countries. So, although the 123 other countries that have ratified the treaty could bring a prosecution against him and even issue an arrest warrant, the ICC has no power in Russia. Additionally, the ICC refuses to hold trials without the defendant being present, and it's hard to imagine Putin showing up for a trial. So the only route for a prosecution in the ICC is for an arrest warrant to be issued and then for Putin to go to a country that ratified the treaty. For example, he'll be promptly arrested and transferred to The Hague in the Netherlands, where he would stand trial before three judges. If the majority of these judges found him guilty, then he could be sentenced to up to 30 years in prison. The thing is, though, that Putin would know of the arrest warrant before leaving and would therefore just avoid these countries.

Of course, this would make international diplomacy pretty difficult, but given recent actions, Putin probably won't be doing much of this anyway. Regardless of whether Putin did end up in The Hague, part two of the Rome Statute, the statute that establishes the ICC, outlines four different crimes that the ICC has jurisdiction over. The verse defined in article 6 is the crime of genocide, in effect, the systematic killing of members of national ethnic or religious groups. The second crime is a crime against humanity, with this being murder, extermination, torture, apartheid, rape and a whole load of more terrible crimes. The third category is war crimes, or in essence, a violation of the Geneva Convention. This would include unlawful killing, the targeting of civilians and the destruction of infrastructure that is key to their survival.

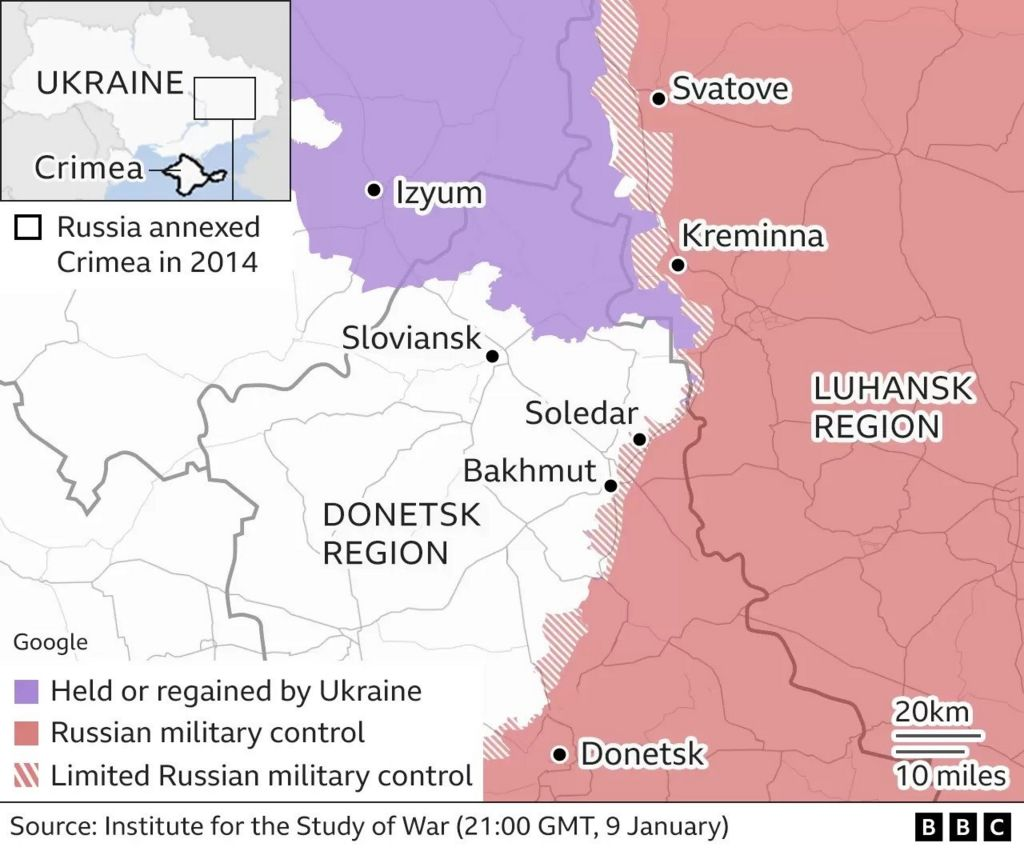

Putin could plausibly be charged with all three of these crimes, and is almost certainly guilty of the fourth and final crime on the list. It's defined in a recent amendment of article 8; it's the crime of aggression. This is when a state uses its armed forces against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another state, which he's pretty clearly guilty of. So, in summary, it could be reasonably argued that Putin has committed all four crimes that the ICCC has jurisdiction over, but it'll be difficult to get him there. So what other routes are there?

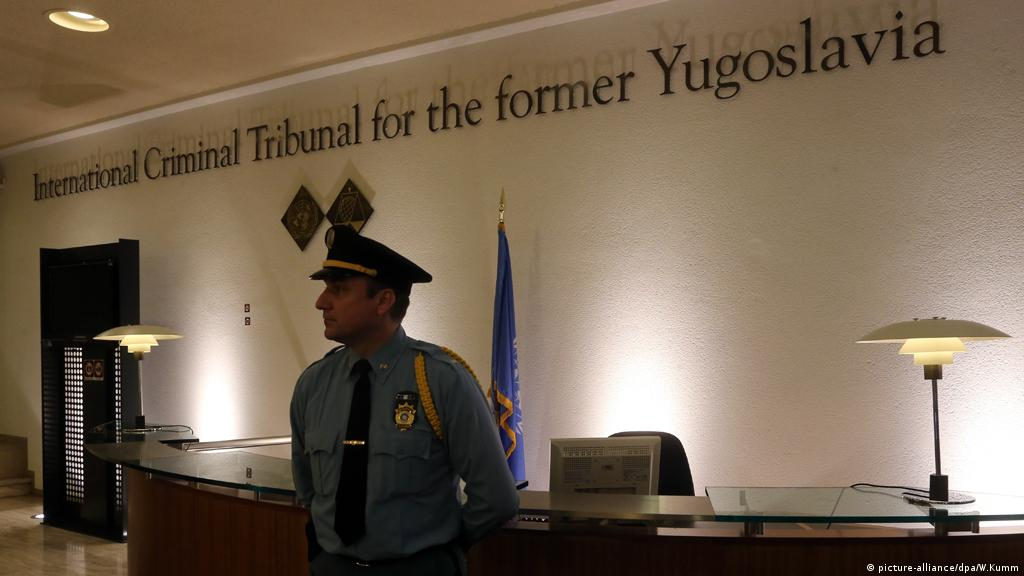

The next possibility is a dedicated ad hoc tribunal from the UN. Unlike the ICC, the U.S. does not have a permanent court that prosecutes individuals for the crimes listed above. Instead, it can create ad hoc tribunals that look at whether a state or individual has committed said crimes. A good example of this is the international criminal tribunal of the former Yugoslavia. This tribunal was set up to address the war crimes that took place during the conflicts in the Balkans in the 1990s. It had jurisdiction to investigate individuals, and it also had the jurisdiction to investigate individuals who are accused of breaching the 1949 Geneva conventions. The ICC investigates similar violations of the laws or customs of war, genocide, and crimes against humanity, similar to what the ICRC does.

Like the ICC, the ICTY was also passed in The Hague/Netherlands. In total, the ICTY called 4650 witnesses and included more than 2.5 million pages of transcripts, ultimately delivering 161 indictments. One of the most notable trials was that of the former president of Serbia, who was accused of genocide and died whilst on trial. So the UN could establish a similar tribunal for Ukraine, but unfortunately for anyone who wants to see Putin behind bars, the same problem arises. How do you get Putin to The Hague?

There is a third route through a military tribunal, but this one too faces a similar problem. A military tribunal is essentially the same as the UN route, except that it's organized by a group of interested countries outside the UN or the ICC. So it could be organized by the US, for example, and a good example of this is the Nuremberg trials that took place after the Second World War. This is also unlikely, though obviously, Putin would be unlikely to recognize a US-led military tribunal and, admittedly, it would lack the legitimacy of an established international court. Also, when the Nuremberg trials took place, the UN was only weeks old, so it wasn't ready to take on such a big case. These days, though, that's no longer true and the UN is likely a better outlet for this kind of thing.

So if those three options are all flawed, let's move on to the fourth and final route, domestic legislation. To be clear here, we're talking about other countries using their domestic legislation to prosecute Putin, not Russia prosecuting Putin himself, which is unlikely. Anyway, in law, there's a principle known as universal jurisdiction, and the ECHR explains the principle as a state's jurisdiction over crimes against international law even when the crimes didn't occur on that state's territory and neither the victim nor the perpetrator is a national of that state. In essence, anyone can try anyone when it comes to international law.

Germany has already started to investigate Russian forces for crimes against humanity, and there's a good chance that Putin himself could be included. Though the same problem arises again: even if Germany finds Putin guilty in his absence, the only power they'll have is to promise to arrest him if he ever enters Germany, which isn't that big a threat. In all, whatever laws Putin might have broken, a successful conviction looks unlikely because, well, it's hard to imagine him handing himself over anytime soon.

Comments